Glastonbury Unsung Heroes: Behind the Wheel with Ethan Harrison

Ever wondered what keeps the greatest show on Earth running smoothly behind the scenes? While the roar of the crowd and the iconic acts on the Pyramid Stage grab the headlines, a dedicated crew works tirelessly to build and maintain the festival’s intricate infrastructure. We caught up with one of the crew, Ethan Harrison, a Glastonbury veteran who drives the ubiquitous yellow machines around the site (as well as writing multi-media novels, designing board games, and with a backround that reads as being as long and varied as the Glastonbury line-up is diverse), to get an insider’s perspective on his vital role.

From Litter Picking to Festival Logistics

John: It’s good to talk to a fellow… I don’t know, what do you call those of us who have worked the festival for all these years… Glastodians? Tell me what it is you yourself do at the festival?

Ethan: (Laughs) I like that! These days, I’m primarily focused on driving, but I still have the dirty fingernails and feel the pain of my sore feet! It’s impossible to have feet that don’t hurt and clean fingernails here, whatever you do.

John: So, what exactly is your job description down there now?

Ethan: I drive one of the yellow machines that go all over site. That’s what we do these days – we deliver the furniture. Most of the large venues have catering, they also have public seating, you know, and there’s the hospital, the medical, the stewards, everybody. So, there’s thousands upon thousands of chairs and thousands upon thousands of tables, and they all need taking out and then picking back up again, bringing them back, counting them, and putting them away. That’s the major thing, the chief responsibility.

John: That sounds like a massive undertaking.

Ethan: It is! In the old days, 20 years ago, we used to do everything by hand, basically. We used to load the trucks – about eight of us in a chain, hand-loading the articulated lorries. About 700 tables in a lorry. That took a long time, and it was very tiring. Now we do it all mechanised, basically. So, it makes us a lot quicker, and we can do a lot more, a lot sooner, and a lot more efficiently.

A Festival-Forged Career Path

John: So, the driving, the mechanised furniture supply. Did you have those driving skills to start with, or did you learn those as a result of the Glastonbury demands?

Ethan: It happened because I got a job at Glastonbury. So it’s through the festival. I was in logistics before, I was a driver before, but it was my driving license that got me in, because it was clean, and they got me the job at Glastonbury, where I’d always wanted to work. I’d been coming here for 20 years beforehand, but I was staying around longer and longer. I did the litter-picking one year, and then somebody came looking for drivers and said, “Who can drive a tractor?” And I said, “I can.”

I can’t recall if I ever actually had up to that point, but if not I sure learnt fast.

Now, every summer it’s been on, I’ve been here. And as I say, through this, I’ve become fully employed in other festivals, and that’s pretty much what I do now. The importance of the festival to me is enormous, on a personal and professional level, I’d probably put in societal as well, along with most of the people I’m hanging around with.

The Next Generation and Lessons Learned

John: There’s always this thing about where the next generation of people like yourself is coming from. Are there young kids, people 30 or more years younger than you, coming in now in the same kind of way?

Ethan: In our crew, there are a few newbies this year. Sometimes we take more than others. We’ve got two newbies this year, but the even the rest are all still relatively young compared to me. I’ll say this now, I think I’m older than most of their parents!

Yes, we do have young ones coming, you know, 20s, 25. I think 25 is the driving age here, I’m not sure about that, you might have to check. But they are, yes, in comparison to me…children! But they have a whale of a time because there are people here that have been doing this work for decades, so the younger ones get initiated quickly, and they get told a lot of things not to do instead of having to learn those mistakes themselves. The experience is sometimes, well, it’s very useful, in fact, here. It can be critical, let’s face it.

John: What’s the biggest mistake you’ve made that you’ve learned from here, or at any festival, really?

Ethan: Hmm, that’s a very good question. I’m currently making a board game called “The Festival Game,” which is one of the indications of my involvement in the culture. Festivals have probably become the heart of English culture, let’s face it, now that nightclubs and pubs have died.

For the game, we had to find out all the bad things that happened to people at festivals to make the cards out of. So I went around to people for years saying, “What’s the worst thing that could happen at a festival?” Losing friends seemed to be a popular one, I suppose that used to happen a bit more before the advent of smartphones.

What’s the worst thing I’ve done? Ah, I know, but it’s definitely not publishable!

But if you go on your own make sure you’ve got good footwear and loads of money, and you’re in a good frame of mind, and you’re funny, and you don’t mind getting wet or soldiering on, as the Brits like to say, you’ll have a good time.

As for a mistake I’ve made, I don’t know, really. I’ve been to so many events, I should think I’ve done everything that you shouldn’t do: not eaten properly, not slept enough, not drinking enough water. I got really bad cramp one year, and that was from not drinking, and that was about as poorly as I ever got, because I couldn’t get out of my caravan. My legs just locked up, and I was in agony. So, not drinking enough water – you really must publish that! It’s sound advice for any festival-goer: drink water. If you drink water, you’ll be fine. Unless you’re drinking it from a puddle. Don’t do that. Try and drink out of a bottle.

John: I was just going to share a story about a professional mistake that somebody apparently made at Glastonbury years ago. It was one of the really wet years. I kind of turned up late to the party, but I was told that the dance tent kind of flooded inside. So somebody thought it would be a good idea to try and suck the water out using one of the muck spreaders. And the spreader went backwards…

Ethan: That’s the one! That’s definitely on one of my cards! I think we played the game about a week ago, and it was the third card somebody got: “You get sprayed by the muck spreader,” and they weren’t happy at all. Yes, that’s cultural, that’s legendary. That’s part of English folklore now. It is literally that kind of popular – a meme, if you like, a legend, a myth, well, it’s a truth, isn’t it? It did that! It’s retold millions of times. That’s an ancient Glastonbury legend. It’s the beating heart, isn’t it? Things like that kind of come from here.

The Cultural Heartbeat of Glastonbury

John: How do you sum up Glastonbury?

Ethan: It’s the World Cup of culture and the FA Cup of festivals, isn’t it? I mean, it’s this place, really, and I’m part of it. I’m very proud, and I’ve been very fortunate. I must have seen every performer from Mick Jagger to Blondie, to Brian Gibb, to Elton, to The Rolling Stones, to Paul McCartney – everybody. All you have to do is come every year, and in the end, you’ve seen everybody.

John: That does answer one of my questions, which is, it sounds like during the festival, you get a bit of time off to actually enjoy it.

Ethan: I see more bands when I’m working! (Laughs) When I’m off, I tend to rest. It is quite hard. We’ve got a lovely camp to ourselves. Although I am, again, extremely fortunate. I live for the duration in my caravan down the world-famous Muddy Lane, which used to be the entrance, I believe, in 1984 or whatever, when I first came. From my audio vantage point, I can hear somebody fart on the main stage, basically. The sound up here is perfect. It’s like I’m right in front of the Pyramid Stage. For one reason or another, up here in the hedgerow on Muddy Lane, the sound carries perfectly from the Pyramid Stage. So I can literally – I don’t want to make anybody jealous – but I can lie on my caravan chair seat with the window open and the hedgerow next to me with the birds tweeting in it, with Elton or Dolly Parton wafting in through the window. I’m very, very lucky. It’s a marvellous place to sort of relax and listen to what has become this kind of cultural monolith.

John: And of course, it’s the diversity of the place. Having booked a stage myself, and seen it from the inside, it’s not exactly unique completely, because I think most festivals have this to an extent, where each area is kind of programmed by someone independently. But I think it’s the sheer level of independence at Glastonbury. I’m pretty sure that other festivals have a bit more of a central programming control system set up, whereas Glastonbury a lot of the stages literally book themselves.

Ethan: Yes, they do have a unique feel to them, I would agree. My other big festival is Boomtown, but that has its very own vibe… it’s really just for your younger audiences. Here, you get that. I think Glastonbury’s success is because it’s the width of the demographic, because you get kids and old people mixing it up, and it makes the young people behave themselves and they relax a bit more, and they don’t just spend all the time texting each other and posturing. Everybody joins in in a different way. It’s like a universal demographic, age-wise.

When I used to play records to people as a young man in the ’90s and ’00s, I did a lot of professional DJing, and my favourite gig, because it was always the best atmosphere, was a wedding, and it was because there were kids there and old people. By six o’clock or four o’clock, depending on which wedding, when everybody had had enough to drink, the atmosphere on the dance floor was the best, I thought, because you could actually get away with the most variety with the records, and it was broad, you know. They don’t expect just drum’n’bass or techno or whatever, you could just play happy stuff, anything, and everybody was up for it. And I liked that. And I thought, “Oh, Glastonbury’s a bit like that,” because it’s almost like a big family party. It’s not surprising to see people who aren’t necessarily of the same age partying together, which is good, I think. It’s a more reflection of society as a whole.

John: I couldn’t agree more. But I think, one of the things that has shifted in a big way at Glastonbury is there are a lot, lot more DJs than there ever used to be.

Ethan: I agree. At one point years ago, they used to play some records after the last act of the Pyramid Stage, and everybody, because everybody was effectively in the same field in 1986 or whatever, everybody got to hear the same record. I think they played “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” they played “London Calling,” and everybody listened to it, and everybody clapped afterwards or cheered. And I thought it was a really nice kind of universal, sort of bonding moment, which was quite remarkable to me when I’d never seen it before.

John: I always remember during the mid-to-late ’90s, the DJ culture actually used to come from the stalls. When you’d walk around the stalls, they’d all have little sound systems…

Ethan: Absolutely, everyone remembers Jo Bananas, “This is a shop for a party. Let’s stay up all night.” And back then I remember it was a free-for-all, I think, ’89 or ’90, down in the valley at the bottom. I can’t remember what field it is now because it’s changed so much, but there were a good four or five sound systems, and you could listen to three records at once if you stood in exactly the right place. And people just bought their trucks and started playing records.

Actually, I remember now, it was ’89 ’cause it was a lovely summer and it went on until the Monday, I think. And that was a bit of an eye-opener.

I really don’t know what would have happened without Glastonbury. It has that fundamentally keystone-like importance for the rest of everything, really. God knows what would have happened without it. We’d be in a terrible position right now if it hadn’t just properly kick-started the whole festival culture, because you couldn’t convince anybody to come in 1987, say, “Who wants to go to a field and into a tent and listen to reggae music in the rain?”

And then it became de rigueur, and people would kill each other for tickets, you know. And you couldn’t make them go before. It didn’t matter what you said. And I knew it would become the future. So I was just waiting for it. I don’t know, for people to come around to my way of thinking, but it certainly did happen, and I’m not surprised.

John: The global music industry really kind of centres around England, and as you say, Glastonbury kind of kicked off the shift of festivals into the mainstream.

Ethan: And I think to a large degree, everything else that was associated with it as well, because as well as the festival, and I know this for a fact because I was part of everything that was associated with, just alternative lifestyle, you know, pride to a certain extent, and all those kind of movements and workers’ movements, the Red Wedge and CND.

But also, the technical bits as well, and veggie meals – they were at Glastonbury! I remember that. People were going, “I’m not going there, what are veggie burgers?” Because that was niche back then, you know. Solar panels, totally niche. And I remember seeing those at festivals. You know, charging phones, their first practical use that I saw, really, was at festivals. Wigwams, yurts, all that kind of alternative living, new-age concepts and beliefs. You wouldn’t even talk about them without getting a strange look in some villages in the ’80s, but now they’re all overt cultures, as you said. And we’ve all witnessed all these alternative kind of aspects to culture becoming overt. It’s been very, very interesting, watching them slowly being accepted to a large degree. Even wind turbines. Some of the things Michael’s done here himself, you know, the biofuels thing. And a lot of those are sort of interconnected, but they were faced with the same type of dismissive approach, as were festivals. But they all kind of fused together, and now, as you say, they’re mainstream, everything’s mainstream that once wasn’t. So it’s been almost like a successful social experiment, hasn’t it?

John: Well, this definitely has moved into a different realm from where I expected this conversation to be, because I thought it was just going to be about driving tractors!

Ethan: I’m sorry! (Laughs) Tractors…fourth gear. Don’t reverse too far. You’ve got to reverse in a straight line. Don’t muck around with that. Please put the handbrake on. You can cause a hell of a mess if you don’t do that. If you do hit something, keep the speed low. Always have a breathalyzer – we have one every morning. You’re dead slow on the event, and be courteous and always put your thumbs up to people going past, so they know what you’re going to do. Try and indicate. There you go. That’s driving. Your 30-second “how to drive a tractor” lesson.

Breaking into the Festival Scene

John: One last thing. If some young, 17 or 18-year-old who’s been to a couple of festivals is reading this and thinking, “That sounds like something I’d love to do,” how would you suggest they go about it? What should they be trying to do? Who should they talk to? How would you guide somebody into the new generation of doing what you’re doing?

Ethan: Right then, to bring it back to driving, which is, after all, despite my other things, the thing that I’ve always kind of gone back to is driving. Get a clean driving license. That’s probably the most important kind of credential or qualification in festival work. Although a lot of people don’t like to face the fact, festivals are all… it’s all about cars. Everything is cars and everything these days is cars and vans and lorries. Nobody these days touches anything unless it’s been on an articulated lorry. It just doesn’t happen. And people would like to think that maybe things get to the house on somebody wearing a flat cap on a baker’s bike, but it just is not the case. So, it’s about haulage, really. We’re logistics. That’s what we do, and everything is vehicles.

So, turn up with a clean, current UK driving license. Be optimistic and have a sense of humour, mate, you’re going to need that. And try and turn up and work hard. The work ethic is crazy. I’ll say that for any prospective employee: you’ve got to want to work hard and turn up and be friendly, and you’ll do well. Just get your foot in, and people will remember you because everybody needs people who can drive, who are friendly, and turn up on time and are reliable. If you’re all those things, you’ll do well.

John: Absolutely. So, you just start driving small things and then work up to the bigger stuff?

Ethan: Just that. Oh, and if you drop any rubbish on the floor and I see you do it, you’ll get the evil eye! But I don’t expect people to do that who come and get a job here, ’cause they’re all really nice kids, usually. So there you go. That’s my advice: clean UK driving license, don’t throw your rubbish on the floor, turn up on time, always pass your breathalyser. That endears you to me. And I suppose, you know, you come in with just a basic car driving license, but if you follow those other tips, you’ll get trained. If you’ve got your own tools, that’s good, because maybe there’s a bit of construction, but usually we just do logistics, we just drive.

Experienced driving as well, that would be better, and driving with a trailer, that’s always really useful, because obviously, much like the rest of the world, with articulated lorries, we need to put things on trailers, because it ups our efficiency. So that kind of truck driving experience, agricultural driving, or driving with a trailer. If you can drive with a trailer and you say, “Yeah, mate, I can do that, and I’ll be there at eight o’clock Monday morning,” you’ve practically got a job.

I know it’s hard for kids these days because a lot of the older employees like me can drive a truck and a trailer on what’s called euphemistically a “grandad license.” The kids have to try a lot harder. They have to do a trailer test and lots of other stuff you have. But that’s what’s required, really. Those almost advanced driving skills.

John: Perfect. And I also hold the “grandad license,” and it scared the wits out of me when I first got it because I’d basically driven a Ford Cortina around the Isle of Wight for a couple of months, and then I passed my test and they gave you a bit of paper and it says, “You can now drive a seven-and-a-half-ton with a trailer.” And I’m like, “Who’s taught me how to do that?!”

Ethan: The world used to be a dangerous place! Fortunately, I was broken into all those things and went kind of slowly up, so I had quite a bit of experience when I got here. Driving at Glastonbury is the super challenge. If you can drive here for ten weeks, which is what I work for while I’m here, and not have one accident, you know, not just tap something, not be over whatever it is. It’s… or not getting in somebody’s way, always parking out of the way. Don’t lose your keys, whatever. It’s challenging. Things are going on. It’s an intense driving environment, sorry. And one has to concentrate quite hard. That’s probably the thing that makes it tiring.

John: Absolutely.

Ethan: My machine is huge, and I have to be careful with it. It weighs a lot – 14 tons or so. That’ll do a lot of damage. In the wrong hands, you can do a lot of destruction; in the right hands, you can work very quickly and very safely, actually. They’re brilliant machines, and that’s why I like using them. I’d much rather have been a pilot than work back in the old radio room pushing bits of wood around on the map of England. No, I’m doing the cockpit bit. There you go.

John: Anyway, you’ve given me a massive amount of your time, loads of information, but I understand you are also an author – I can just look you up and find you on Amazon or something like that? You don’t go under a pen name or anything, do you?

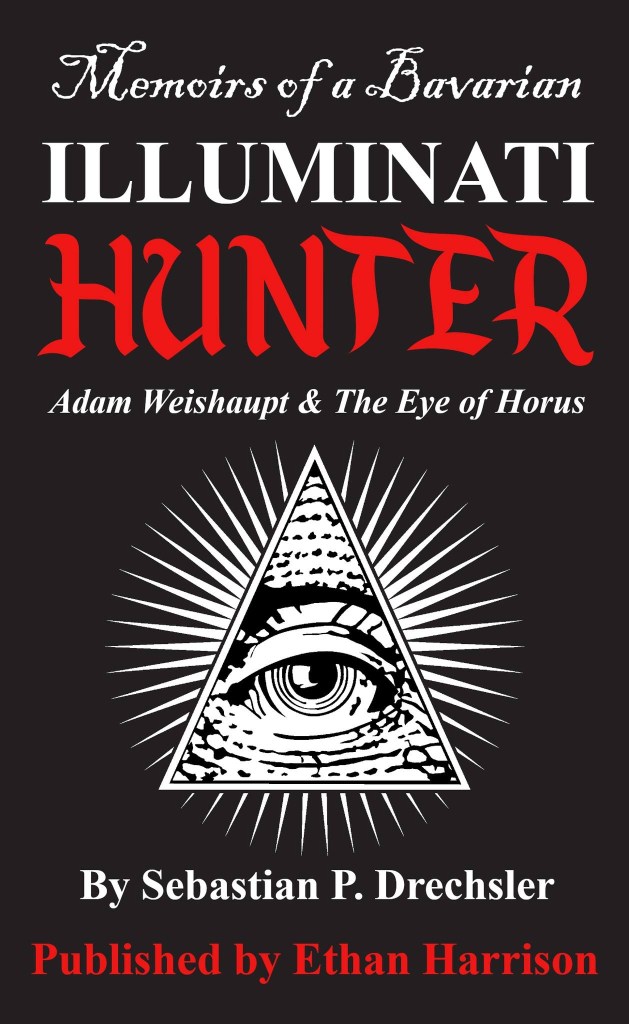

Ethan: Yup, I write as myself. It’s called Memoirs of a Bavarian Illuminati Hunter, and I believe it’s the first book that’s ever properly connected up to the internet, so it’s got 3D maps in it, Wikipedia, the footnotes turned into hypertext links, and it’s got music in it and Mozart and Bach and videos, and it’s very, very novel, let’s say, if you pardon the pun.

John: Thoroughly novel! So it’s a full multimedia experience?

Ethan: It actually is. It’s really good on an e-book. It’s gold dust. It’s brilliant. I can’t see why everybody doesn’t do it. It’s got sound effects in it. It’s fantastic. You can do that if you want to, you can go down the rabbit hole of the book to an extent, or you can just read the book if you like. But it’s a kind of action adventure daring-do with some romance and some one-liners, and kind of decent, traditional, slightly cliched romps, really. Lots of people like it. I’ve sold thousands.

John: Fantastic!

Ethan: That’s me supplementing my wage at the festival, but that’s something the festival paradigm is allowing me to do because I work really hard in the summer. Then I get four months after to go write a book or something, and I don’t think I could do it had I spent my life working nine to five.

John: I have to say when I saw something that you posted on Facebook, I just thought, “Oh, you sound like an interesting bloke who drives tractors at Glastonbury, I’ll see if I can get a little story out of you.”

Ethan: Ha-ha, of all the things I could be, I would be quite happily be pigeonholed as “interesting.” There you go. So yeah, I’ll go for that.